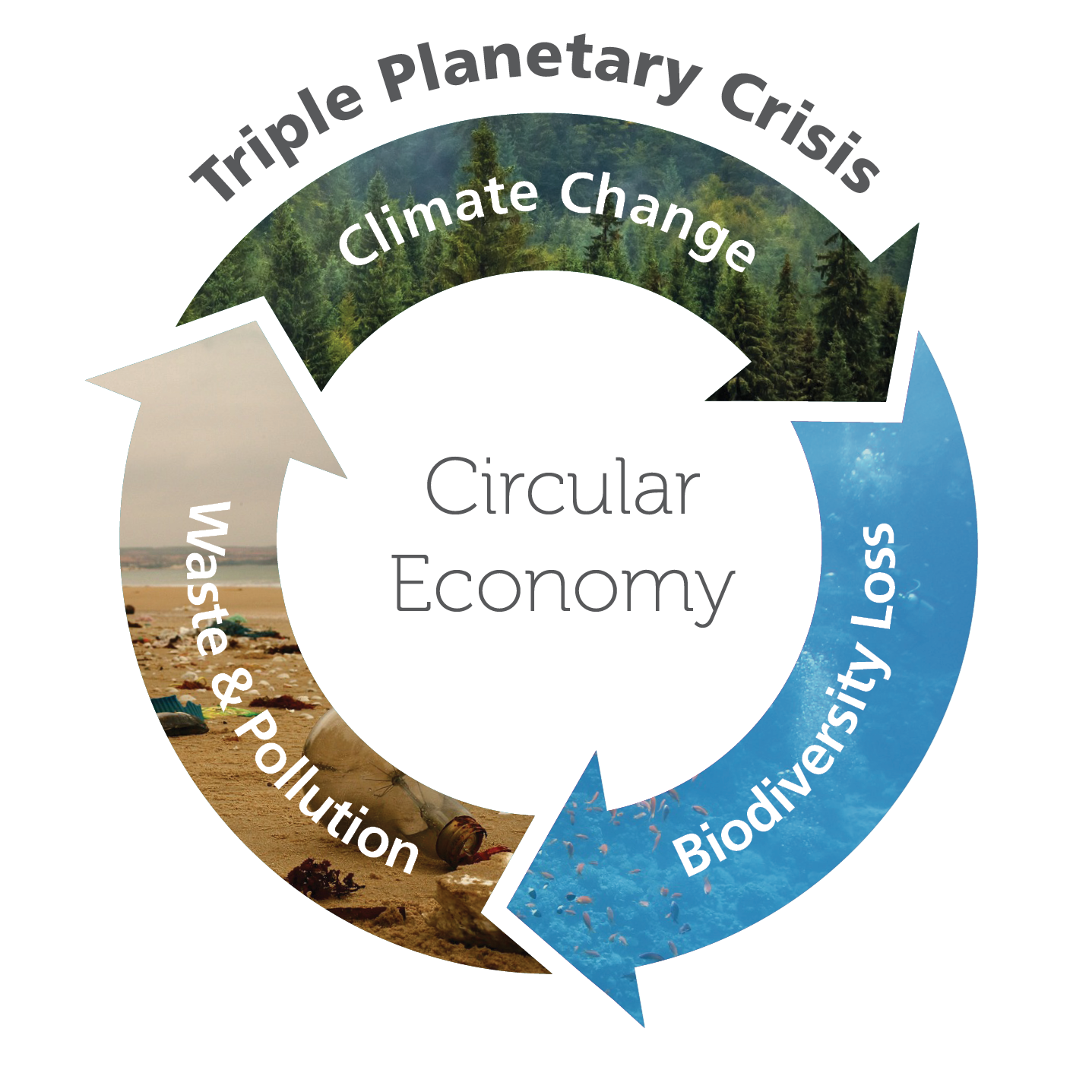

In a world grappling with the impacts of climate change, environmental degradation and alarming levels of waste, we find ourselves in the midst of the triple planetary crisis; of climate, biodiversity loss, and waste and pollution.

In this article, Tania Hyde, Technical Director & Circular Design Lead (Transport & Infrastructure) at Beca, shares her views on these drivers for holistic, systemic change, and discusses the need to transform our traditional models and approaches.

We are at a tipping point, where it is now critical we go beyond conventional approaches to waste minimisation and recycling, and transform our linear model of production and consumption into an interconnected, regenerative, and restorative system. We need to catalyse a circular economy.

The Linear Economy: Our take-make-dispose approach

For over two centuries, our economy, industries, and consumption patterns have followed a linear 'take-make-dispose' model, assuming an endless supply of resources. However, the reality of dwindling natural resources now confronts us, as our current consumption surpasses Earth's capacity to renew. This imbalance threatens future generations, highlighted by the fact that if global consumption mirrored that of Aotearoa New Zealand, we'd already require 3.59 planets' worth of resources.

As one of the highest waste-producing nations in the OECD, we have huge amounts of rubbish going to landfill, stockpiles of recyclable waste, and escalating carbon emissions that are stretching our waste management systems to their limits. Waste minimisation and recycling have long been the cornerstone of our waste management strategies, playing a vital role in reducing environmental impact. But now the Ministry for the Environment's new Te rautaki para / Waste strategy is more essential than ever. This roadmap will guide the action desperately needed for the next three decades, for a low emission, low-waste society built upon a circular economy.

At the World Circular Economy Forum this year it was estimated that even if we could recycle and recover all recyclable waste, by 2050 we would still only meet 20% of the world’s material demands. This was supported by World Bank Environmental Economist Valerie Hickey who said, “We can’t simply recycle our way to a circular economy and a liveable planet.” Ultimately, waste management is the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff – an unintended consequence of poor design. What we now urgently need is transformational change.

Understanding the Circular Economy: A paradigm transformation

A circular economy delivers this paradigm shift – one that decouples resource use from economic growth and ensures that materials, products, and resources circulate in a continuous, regenerative loop. A circular transition will require a bold mindset shift for policymakers, planners, designers, and industry to rethink how we design, produce, consume, and dispose – in ways that design out waste and pollution, cycle materials and assets, and regenerate natural systems. This requires radical collaboration, partnerships, co-design and trust, to enable planning and design horizons to become intergenerational, and develop infrastructure that supports interconnected material flows.

Circular spatial planning is a key part of this mindset shift. Traditional ways of planning can no longer cope with the complexity and uncertainty that our cities and regions face. Increasing social, economic, and environmental risks such as migration, climate change, water challenges, energy demands, technological shifts, and globalisation demand a new approach. We need to reconfigure our urban infrastructure, buildings, open spaces, and connections between cities and the countryside to support closed-loop value chains.

Transitioning to a Circular Economy: From strategy to implementation

The transition to a circular economy is complex and dynamic, and while frameworks exist, there is no single, commonly agreed approach. But theoretical models are not enough to catalyse the shift – our challenge now is to bridge the divide between strategy and implementation.

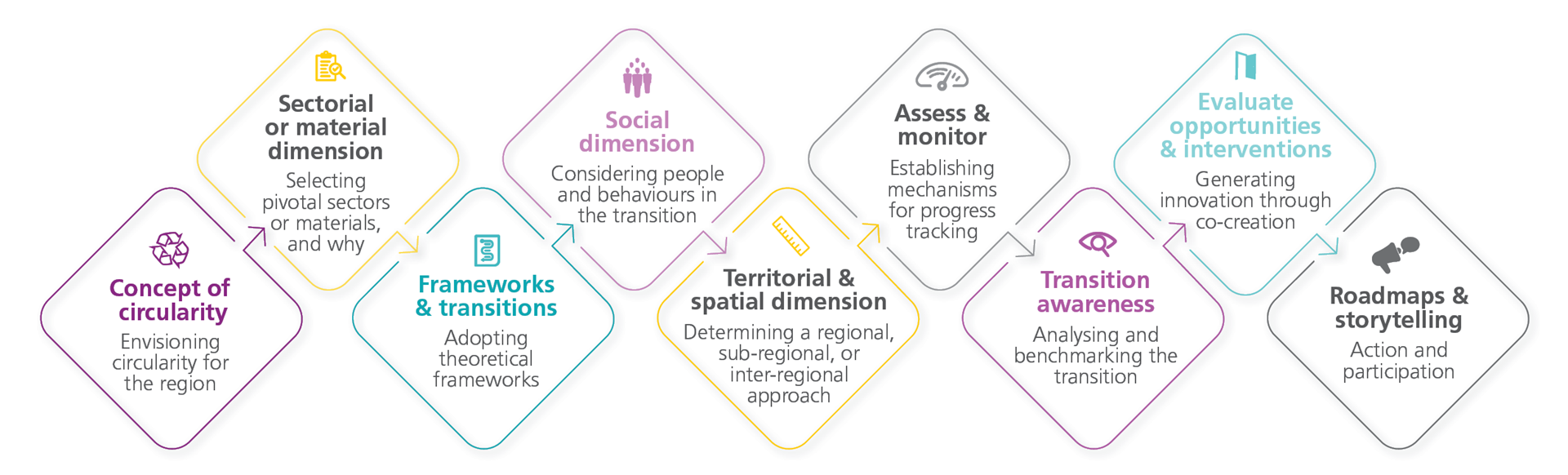

To delve deeper into what facilitates an effective regional implementation, I took a course on circular spatial planning from the leading university in this field, Delft University of Technology. I learned that we must apply an integrated and multi-dimensional approach to guide our regional value chains toward a circular transition. This approach is described below, including some insights on how we could apply the principles in an Aotearoa context.

Concept of circularity

It’s evident that we can’t do everything at once – and this approach prioritises key success factors for implementation. We need to ask ourselves: do we focus on value chains (activities that bring products to market) or R-strategies (shifting design up the R-hierarchy from resource ‘recovery’ and ‘repair’ through to the more fundamental shift in approach and mindset needed to ‘reduce’, ‘rethink’ and ‘refuse’)?

The answer will be different for individual businesses or sectors. The key is to pick one of the strategies and start your journey!

Sectorial or material dimension

Should we focus on sectors e.g., the Built Environment or on specific materials e.g., cement or steel? A specific material focus provides better insights to material flows e.g., what and how much goes to waste or adds value, while the sector approach provides easier opportunities to engage with stakeholders to identify system change.

As a country, we need to look at our data to understand our biggest opportunities for impact before choosing our dimensional focus.

Frameworks and transitions

The real-world experience of countries like the Netherlands (assessed in 2023 by the Circularity Gap Reporting Initiative as 24.5% circular) can offer us valuable transition insights. They have several regional approaches that focus on implementation.

We need to consider: will experiments and pilots accelerate our change at a business level or do we look for planetary boundaries and social aspirations that bring our communities on the journey?

Social dimension

As with all projects and initiatives to deliver practical, sustainable and resilient outcomes, it is essential to consider how local and national communities might be affected by a transition to a circular economy.

For example, do we see people as consumers or users? How are we considering social justice, thriving healthy environments, and public participation in decision-making?

Territorial and spatial dimension

Many policies and strategies differ at national, regional and city level and we need to understand how they are interrelated and complementary. Often the policies have different responsibilities and governance, and this can be reflected through the initiatives and ambitions of each region.

Which spatial dimension approach are we taking: where space (or area) is seen as a container or where problems/solutions are dealt with on a principle or typological solution across borders.

Assess and monitor

Amsterdam provides a valuable case study for the successful implementation of a circular economy roadmap. Key learnings of what went well, or not so well, shows us that we can’t underestimate the importance of intensive cooperation between government, business, and scientific sectors.

How do we know if we’re on track, how will we measure progress: Our current focus is on input/output indicators e.g., waste volumes or volume of recycled material. We need to move beyond these factors to understand our planetary boundaries, natural and social indicators e.g., using the donut economics approach.

Transition awareness

Often circular transitions are complex, involve a huge array of ‘actors’, happen in silos, and vary in their ambition and progress. Being able to assess a region or city’s pathway to circularity, compare it to baseline (or other regions), and adapt the journey is important.

Why do we need transition awareness: 1) to steer conversations involving multiple stakeholders with diverse backgrounds and 2) to make sure socio-technological aspects are not all that’s included, as we often miss spatial, governance, and societal aspects.

Evaluate opportunities and interventions

The evaluation of complex challenges, using systemic design to integrate spatial and transition activities to support innovative solutions through several defined interventions, is critical to success. This is where design thinking and systems thinking combine!

Core to the transition is the exploration and evaluation of the complexities of supply chains, material flows and spatial interactions, to enable a redesign of the system. Understanding system boundaries, value supply chains, and quantitative assessments to support circular outcomes is key to the success of a circular transition.

Roadmaps and storytelling

The ability to provide compelling narratives, to generate support from all actors to achieve long-term circularity is critical to success. Clearly articulated roadmaps enable people to understand the opportunities and become invested in the transitions, allowing them to formulate their own plans and strategies.

Roadmaps and storytelling should be robust, evidence-based approaches that set the context, strategy and action plan to answer questions like: how would a circular region function, what does the desired future look like, and how will it enhance the liveability of our communities?

What’s next? Aotearoa New Zealand’s circular transition

Aotearoa New Zealand’s transition challenges are very real. Compared to many countries, we have a small, dispersed population in a geographically challenging environment.

Yet as we embark on our journey towards circularity, there’s no need for us to reinvent the wheel. Learning from those who have already embarked on this journey around the globe – understanding different approaches’ successes and failures – allows us to adapt relevant insights.

By leveraging discovery, disruption, and data, we can use this opportunity to leapfrog ahead and accelerate the transition from our waste-driven linear economy towards a circular future, shaping a better world for ourselves and generations to come.

At Beca, with our strong sustainability focus and long history of working in partnership to help shape inclusive, resilient outcomes and communities, we’re excited to be part of the solution.

Tania Hyde

Technical Director - Civil Engineering